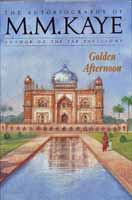

Reviews of 'GOLDEN AFTERNOON'

The second volume of M M Kaye's autobiography. Returning from an English boarding school to India in 1927, Mollie Kaye plunges into the glories - and embarrassments - of the Delhi Season. But more than the social life of the Raj, she rediscovers her love for the country - the magic paradise of Kashmir, the sun-scorched plains of Rajputana, the teeming life of the markets and the complexities of high-caste life. Spiced with humour, incident and her trenchant views of the world, both then and now, Golden Afternoon is suffused above all with the enchantment that is India.

The second volume of M M Kaye's autobiography. Returning from an English boarding school to India in 1927, Mollie Kaye plunges into the glories - and embarrassments - of the Delhi Season. But more than the social life of the Raj, she rediscovers her love for the country - the magic paradise of Kashmir, the sun-scorched plains of Rajputana, the teeming life of the markets and the complexities of high-caste life. Spiced with humour, incident and her trenchant views of the world, both then and now, Golden Afternoon is suffused above all with the enchantment that is India.

Here are some reviews:

* * *

Diamond in the Raj: A Novelist's Rambling Reminiscences. M.M. Kaye wrote three wonderfully colorful and beguiling novels set in India at the time of the British Raj. "The Far Pavilions," "Shadow of the Moon" and "Trade Wind" are full of drama and feeling for the subcontinent and its painful history, with Indians at war with Indians and the British assuming that might must always be right. It would therefore be reasonable to assume that Kaye's autobiography would be more of the same, with the additional spice of being "real life."

Sadly, not so. "Golden Afternoon" is the second volume of "Share of Summer" (the first, "The Sun in the Morning," was published in 1990). Although the title of the new chronicle sounds like the conclusion to a life saga Kaye is now in her late eighties - the golden afternoon refers to the years she and her family spent in India when she returned in 1927 from her boarding-school years in England. Despite the time lapse between the publication of the two books, Kaye regards them as one, as she scatters the pages of the second volume with obscure cross-references and plaintive queries to her readers, such as "Did I say something of the sort in the first volume of my autobiography?"

But it is perhaps ungracious to quarrel with the rambling, almost inchoate nature of these reminiscences, in which we are introduced, for example, to a young lady, a member of "the fishing fleet" out from England in search of a husband, only to lose her a paragraph later when she becomes "Lady Something-or-other to do with biscuits." These vignettes are more constructively viewed as the raw material of an astonishing historical interlude. No one has ever satisfactorily explained why representatives of a small, rainy island in northern Europe should have come not only to rule over this vast and disparate subcontinent but also to think it legitimate to impose their systems of social intercourse, justice and governance developed over centuries on an entirely different world.

These questions may be on the minds of historians, but young Mollie Kaye was enthralled by the sights and sounds of India that she had missed so sorely during her exile in England. She and her sister disembarked from their ship and drank in "the sights and the sounds and the smell of Calcutta, as though we were a pair of parched travellers in a desert."

Looking back, more than 60 years later, she relishes memories of an elegant social life, amateur dramatics dances, polite young men, the absence of intrusive sex and the presence of her adored father, known as Tacklow. He emerges as the dominant figure in these memoirs. One of the unsung heroes of the often-vilified colonial administration, Tacklow clearly had India's best interests at heart though he was not always able to achieve what he wanted. Mollie adored him. Tacklow, his daughter tells us, "had always been both my touchstone and my private Oracle of Delphi." In fact, the most impassioned part of this account involves Kaye defending her father's involvement in a complex misunderstanding about hereditary jewels in a small state with the entrancing name of Tonk, where Tacklow was advising the nawab.

What Mollie shared with Tacklow was a passionate love of India, and when her love of the country bubbles over in affectionate remembrance, there are moments of almost lyrical beauty. Kashmir, the favoured retreat from the heart of the plains, entranced her then, and the memories have not dimmed. There were no crowded streets in the Kashmir of the 1920s. To go home, the Kayes were wafted across shimmering lakes to their houseboat "through green willow-bordered waterways, spangled with lily-pads and the brilliant, flashing jewel colours of kingfishers, to emerge into bright sunlight." The intimate black-and-white photos throughout the book reinforce this almost magical atmosphere.

But these moments are few and far between. Mostly, one feels trapped by politeness, listening to nostalgia that frequently tips over into the "things aren't what they used to be" plaint. Of course, nowhere are "things" as they were in the 1920s, but the stark contrast between the teeming, overpopulated, industrialized country that is India in the 1990s and the days of garden parties in Simla or tiger shoots in Pirwa is too much for Mary Margaret Kaye. "Things last so much longer than people," she concludes wistfully. The palaces may remain, but the inhabitants are long gone. Only in fiction can they be frozen in time. The Washington Post by Brigitte Weeks, 4 February 1999.